ArtLab – Interdisciplinary Workshops

Winner of Reading University Impact Awards 2022

Funded by Wellcome Trust, Research Enrichment Grant

ArtLab are delighted to have partnered with Lecturer Dr Alana Skuse to break new ground in our area – resituating scholarly research in the context of clinical health engagements to create meaningful research impacts through art.

Together with Dr Skuse, we advanced academic research into seventeenth-century representations of self-injury in literature that suggest that modern attitudes towards what is now considered a pathological behaviour are very different from those of the early modern period. Repositioning these into a contemporary discourse that is both inclusive and participatory was a challenge.

Through a series of participant-led art workshops, Reading researchers are raising important questions about how we understand and talk about self-injury.

ArtLabs director, Associate Professor Tina O’Connell, worked with Dr Skuse to first devise a series of workshops, drawing on expertise from her links to clinicians from the Tavistock Centre. Based on Artlab’s proven model of bringing together co-researchers for public benefit, these workshops drew together different academic fields, cultures, and age groups, all whom had a professional interest in – or lived experience of – self-injury.

O’Connell and Skuse then worked closely with psychiatry professionals and student co-researchers from Fine Art to create an atmosphere of trust during the workshops. Skilled facilitation and open discussion between participants whilst they developed responses to their own personal experiences of self-injury ran in parallel with a range of artistic and creative projects exploring clay modelling and digital animation.

The artworks created during the workshops create significant insights into response to the issue of contemporary self -injury for the participants and are being displayed as part of a digital exhibition to demonstrate how art-led, humanities-informed models can be used to discuss and destigmatise self-injury in both clinical and community settings. Meanwhile, Dr Skuse findings from the project are being used as the basis for a new academic monograph.

Co-researcher and recent Fine Art graduate Charlotte Thomas reflects on her role in the project:

Week 1

During week 1 of our workshops, Dr Alana Skuse showed us a presentation which introduced self-injury as not only a modern occurrence but also as something prevalent in the seventeenth century. We were informed of self-injury among males in the 17thCentury who performed the act when their wives where thought to be cheating on them. Additionally, we learned about the Amazonian women who were thought to cut off one of their breasts with the hopes of improving their archery accuracy. However, throughout the presentation we discussed the importance of remembering history has been predominantly dictated by the patriarchy. Therefore, when we learn about the history of self-injury and especially those of women, we must keep an open mind to whether these acts were for a personal benefit or acts of brutality from others.

“A very creative project with real strengths in cross-disciplinary working that combines artistic practice and historical context to address an important issue in innovative ways.”

Following the presentation, we moved into a 3D working space and furthered our conversations in small groups about the history of self-injury and how that would change our modern conceptions on the topic. These conversations were held over a session of sculpture making with blocks of clay. Physically working with the clay enabled us to depict the act of mutilating a hypothetical piece of ‘flesh’ or to create a piece of work which delt with the topic in a more abstract nature.

We worked with the material as we discussed Alanna’s presentation, and unconsciously allowed certain forms to develop. The conversation revolved mainly around the feeling that contemporary attitudes to self-harm are concerned with an internal, individual state of mind. The historical view presented by Alanna suggests self-injury as a social phenomenon and therefore less private or taboo.

The manipulation of clay and the use of the making as metaphor, seemed to really chime with my co-researcher and her outcome told the story of our conversation. Her ‘sculpture’ portrayed a narrative of her daughters struggles and where she sees herself within this.

Self-injury has been explained as a form of taking back ‘control’ of oneself and one’s life – the only element of their being that they have any kind of control over. They feel that they want to articulate their suffering by marking themselves externally. There seems to have been a shift from predominantly male self-harm in the historical context to primarily women in a modern context. We also discussed that self-harm seems to be more prominent in women, whereas men may take out their emotions more violently in comparison on others.

It is often something that cannot be explained by the individual self-injuring. It is a compulsion that is carried out in periods of stress and vulnerability and in some respects a form of ‘punishment’ of oneself for being stressed or vulnerable?

Week 2

The second session of the self-harm/injury workshop presented us with the question on what the difference is between self-injury and body modification? We discussed what sort of factors might determine the difference such as, motivation, cultural context, social acceptability, painfulness, and usefulness. Circling back to the conversation’s had in week one it was possible that the Amazonian women’s breast removal could be due to the factor of usefulness as it would aid them in their fighting capabilities. However, through participant discussion we came to realise that factors such as cultural context and social acceptability could greatly play a part in the modification/injury of the women. Thus, highlighting the importance of the workshop to allow this discussion to flourish, enabling us all to continually question our perceived ideas. Furthermore, this session encouraged participants to question whether modification could be a ‘safe’ alternative to self-injury or whether it would encourage people to harm themselves and their bodies more?

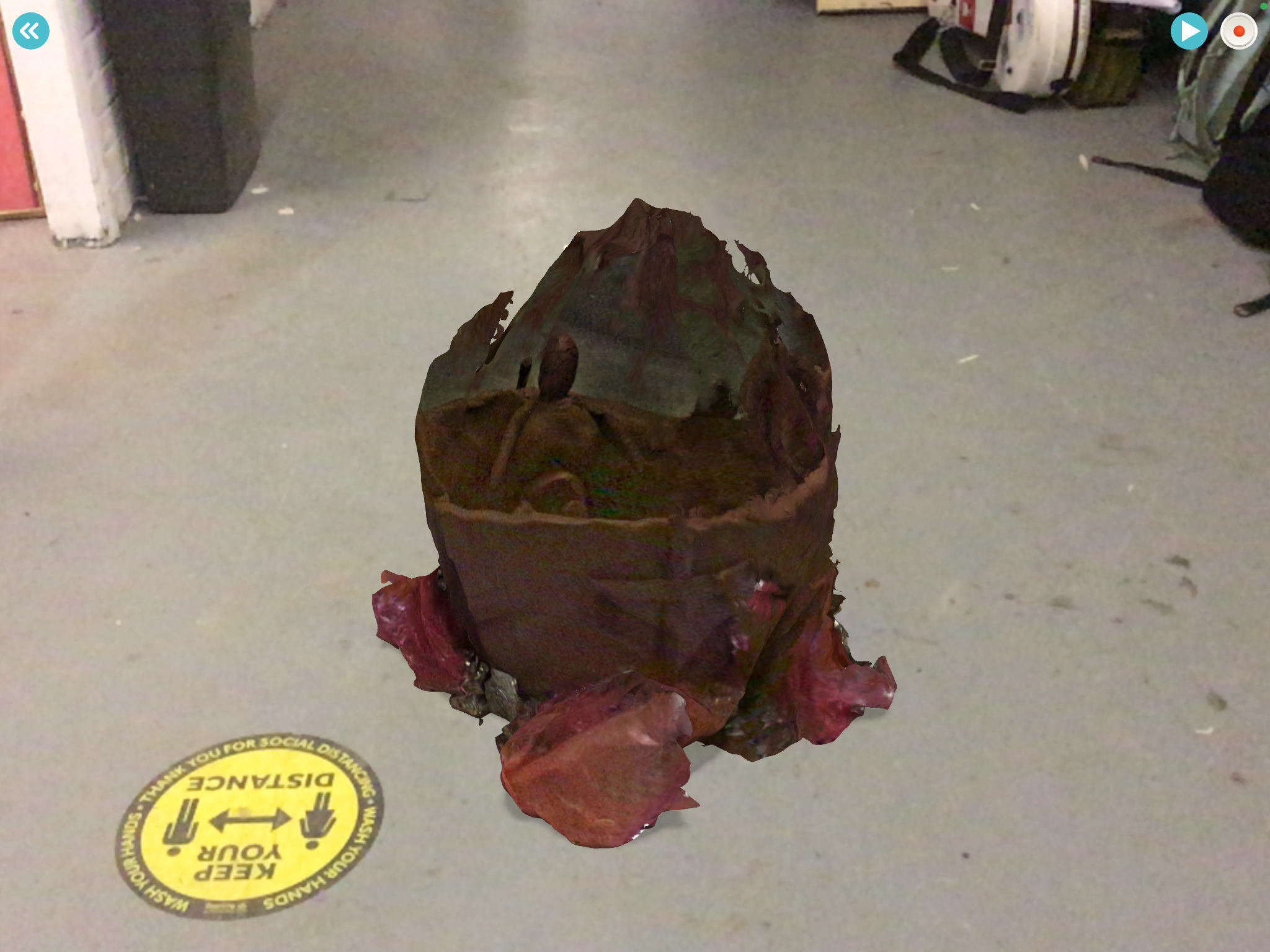

After the presentation we took a similar approach to the sculpting session in week 1. Using the clay blocks to encourage and enhance our conversations around modification and mutilation. Following the creation of the sculptures each group would use the Qlone App on the iPad to scan their sculptures into augmented reality. Bridging a gap between the tactile nature of clay sculpting and the modern phenomenon of cloning technology.

‘We found it difficult to distinguish between mutilation and modification since pain is a major commonality in most cases between the two. However, after considerable deliberation, we concluded that self-injury is seen more negatively due to its impulsive character and is seemingly fuelled by an increasing quantity of negative emotions. Self-modification, on the other hand, was more of an intentional decision influenced by societal trends and culture.’

‘We believed that mutilation was not often a choice and is done in an expression of uncontrollable emotion. We also discussed the trans-experience in relation to this and how the act of modifying the body is empowering to the trans community whereas some people saw it as mutilation.’

‘The discussion was of a reflection of body modification depicting the unusual and sometimes mysterious and mythical historical writings of body modifications, whether feeding the myth of the unbelievable or an interpretation of it. From body modifications of Amazon tribes (a disc that stretches the bottom lip); to cultural tattoos for example Maori tattoos or sailor’s tattoos; to modern day tattooing and body piercings. Each with either a negative or positive reaction and acceptance within society i.e., a negative one where judgement is passed on a person who has a tattoo as being somehow lower within society.’

‘… we talked about how body modification can be different from self-injury in relation to the intended permanence of the action. For example, getting a breast augmentation is a relatively permeant modification to the body, however, if we think of self-injury in the terms of cutting the skin it’s an action that might be intended to modify the body in the moment that will heal in the future.’

‘Some may think of modification as an enhancement in terms of appeal or attractiveness. In our group the point was also made that some modification, like tattoos, is not for any kind of public display but a private relationship with significant events in their life. The pain is part of embedding that event.’

Week 3

During the final session of the workshop a presentation was given informing the participants of the four humors. Humors were the four liquids within the body that people believed in the 17th century controlled one’s temperament and affected their general well-being. The four humors consist of Yellow Bile, Black Bile, Phlegm, and Blood. It was said that to have too much of any one of the humors caused imbalances. Treating the imbalances resulted in an incision made in the individual’s skin to release the liquid. This act of releasing liquid encouraged participants to discuss whether this would be a form of self-injury, or benefits to general health?

With our scanned sculptures, we took the iPad’s outside and placed our augmented reality creations into real life. Projecting the sculptures through the iPad into forests, car parks and places of interest which enabled us to begin to create a narrative around our pieces considering the information about the humors. Additionally, each group was set the task to come up with specific words and sounds which related to their digital sculpture work and the narratives they wished to convey. Taking video recordings of the projections of the sculptures along with voice recordings of our chosen words and sounds, a video was produced from each group depicting their thoughts and experiences over the 3 self-injury sessions.

‘Using the software, we were able to explore the disconnect some feel towards themselves and their body/brain’.

‘… we discussed the idea that the act of cleansing the body is not restricted to medieval humors and is also carried out in ideas of cleanses and diet fads today and whether these are considered acts of self-harm.’

‘The screen recording on the app disconnects you from the process of manipulation with the model, so it looks like the model now has its own self-awareness’

‘This topic brought up interesting conversations around our object in relation to what makes us, and whether purging results in a disassociation with the body.’

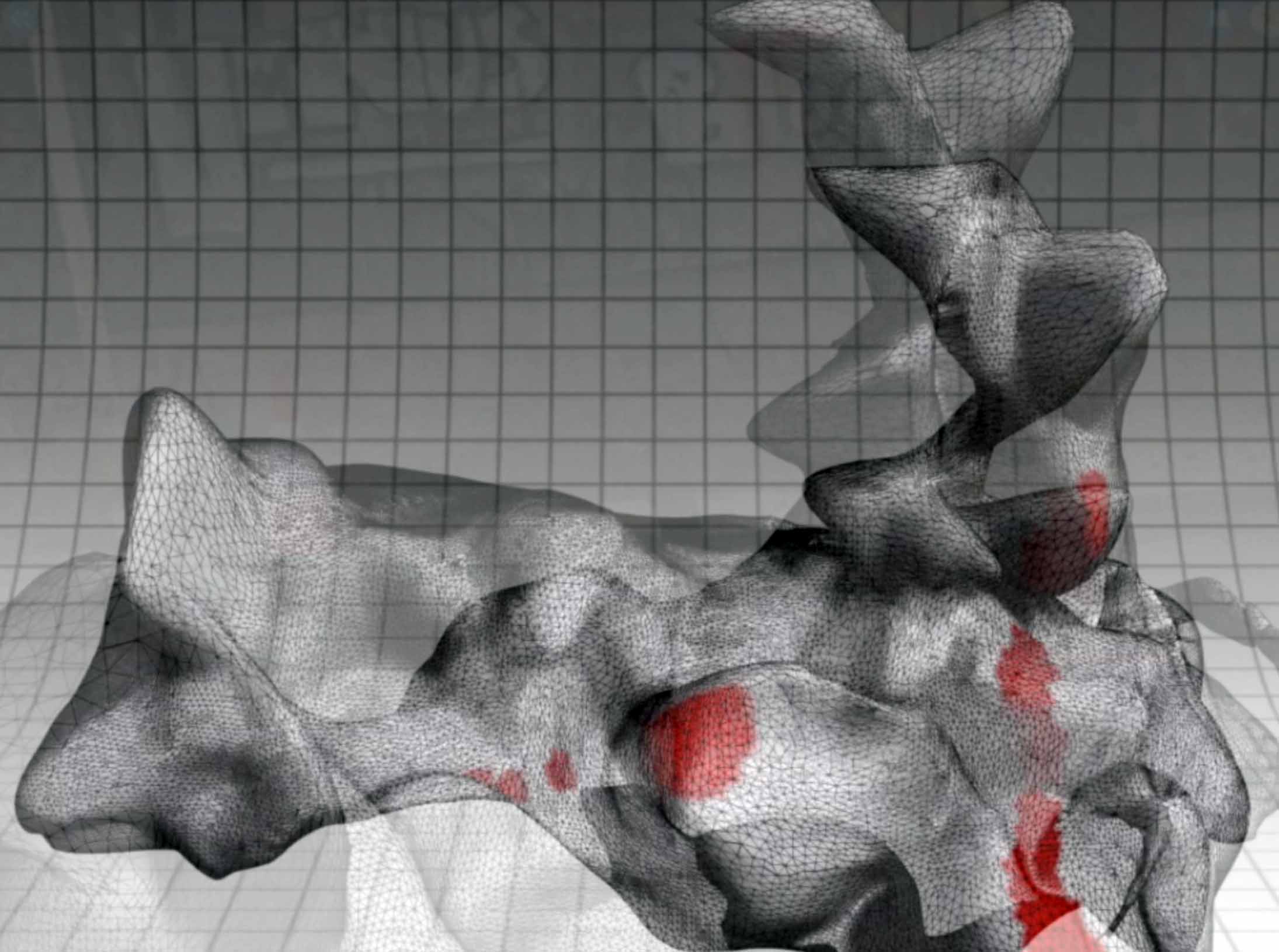

‘…with the digital capabilities of our scanned sculpture, we experimented with the filming process as well as the setting which makes the object crawl and move. this started off a comparison to ‘aliens’ in the object’s relation to the body and how it became a part of it, or a separate autonomous being that relied on the body symbiotically. With this the act of self-harm became a more visceral thing in our work- particularly in the pulling and pushing of the digital clay- modifying it to our liking but accepting a lack of control for it too.’

Co-researcher and recent Fine Art graduate Sophie Baldwin tells us her role in the sessions:

ArtLab gave me the opportunity to engage their collaboration with the Wellcome Trust in examining the serious topic of self-injury. This research project allowed for complex conversations regarding a sensitive subject in an engaging art session. These workshops helped me to understand the interconnection between mental health and expressing oneself through art, whilst introducing participants to new materials and technologies.

ArtLab allowed for a welcoming environment that encouraged participants to share their stories in a safe setting. The workshop had a range of participants from different backgrounds and so was extremely diverse in creative material and storytelling.

Throughout the self-injury workshops, we encouraged participants to engage with both clay and 3D scanning technology. This is important outreach, as many of the participants hadn’t experienced either material before. Through the collaborative environment, we were able to work in groups to create clay objects whilst discussing our experiences with mental health challenges.

This workshop allowed us to have a medium of discussion that we likely would not have had otherwise, as the use of clay could mimic and build reflections of self-injuring. We then were able to use the 3D scanning technology (Qlone) to experience our sculptures in the ‘real’ world. Through demonstrating this technology to the participants, ArtLab were able to create a fun, immersive environment to explore creativity and encourage storytelling.

The use of the AR feature was particularly enjoyable for participants, and allowed for goofy warped objects and silly videos that ultimately led to more comfortable conversation and creative output. Through creating the final video piece and demonstrating it to participants, ArtLab emphasised the diversity and creative potential of combining art and technology to widen outreach and further research.

Each of the participants were very different, yet ArtLab was able to engage creatively and encourage participation. The combination of art and technology caters to different ages and this experience with ArtLab has shaped parts of my practice. Working with ArtLab allowed me to gain experience with a variety of people in an educational art setting. The workshops were engaging, creative, and most importantly accessible and encouraged creative, dynamic experimentation.

Co-researcher and recent Fine Art graduate Eleanor Perriman explains the experience of this project:

ArtLab teamed up with the English Literature department and we were joined by a diverse group of people of many ages and backgrounds. We experienced interesting and varied dialogues which were both both philosophical and creative in every session.

Week 1 Summary– Brutality vs. Function of Self Harm with clay

The session began with a presentation from Alanna on the role of self -injury throughout history, disregarding the act as purely modern phenomena. Alanna’s research found its historical presence situated between the ideas of brutality and functionality and considered the presence of these motivations in modern day, bringing to light the taboos of self-injury consequently. Alanna highlighted this by informing the group about Amazonian women who famously cut off a single breast to improve their archery. An interesting dialogue was then opened about the modern-day expression of self-injury and how it manifests in the different sexes.

The dialogues frequently happened as both a larger group and as smaller individual ones whilst we were moulding our clay objects. Because our conversations were about the conceptual emotions surrounding the topic, our clay objects mirrored this in their plastic forms. Because of the tactile material of the clay and the honest, thought provoking, conversational approach of the workshop, even those who were less familiar with creative practices produced heartfelt abstract works.

“The manipulation of clay and the use of the making as metaphor, seemed to really chime with my co-researcher and her outcome told the story of our conversation. Her ‘sculpture’ portrayed a narrative of her daughters struggles and where she sees herself within this”

“I found the workshop really successful for allowing open and honest conversations about self-harm and mental health.”

“We also spoke about how there seems to have been a shift from predominantly male self-harm in the historical context to primarily women in a modern context. We also discussed that self-harm seems to be more prominent in women, whereas men may take out their emotions more violently in comparison.”

“A way of saying, you can’t see what I am going through on the inside but look how it has manifested itself on the outside and this is the only way I can take control of my internal turmoil and struggles.”

Week 2 Summary– modification or mutilation? With clay

The second week of the workshops was dedicated to the concept of body modification and encouraged the participants and co-researchers to question whether it was an act of self-injury, and if so, to what extent? We looked at the historical modification of the cultural elongation of necks within the Myanmar community, as well as the ancient practice of foot-binding in China, just to name two. We agreed that intention separated the two acts but could all mostly agree that modification could be classed as a form act of self-injury, and thus brought up discussions of the social acceptability of these common acts. In relating this concept back to historical self-injury, it gave us a new context to consider the acts of the past and their contemporary social/cultural acceptance. Again, these acts were considered through the lens of the sexes. Both traditions have innate ties to perceived beauty and desirability within their cultures. This ties to a point made by Alanna in the first week of the workshop, that the patriarchy must be considered within the historical conversation of whether these acts were for personal benefit and pleasure or, in this case of self-injury, purely for attracting men and being perceived as desirable.

We had another session with the clay after this presentation and discussion, again fuelling the conversation through the material as the clay was often likened to skin in the context of self-injury; malleable and fleshy. Many chose to pierce, rip, pull, and add additions to their sculptures after this conversation.

We scanned our works and edited them over the Qlone app, pushing and pulling the digital clay this time and enhancing its textural qualities and colours. The app allowed for a different form of ‘mutilation’, where the object became removed and disembodied from its original form- something we all agreed was very fitting to the topic. Using technology also felt significant in reforming the object, as technology plays an undeniable role in the pressures of modern life as well as enforcing modern day beauty standards.

“Our conversation revolved less around the motivations for self-injury and more about the results. One participant made the point about there being a kind of relief or release in the act, whether from emotional distress or as a substitute from other forms of physical pain. Much of this might be ‘bottled up’ by circumstances or from an inability to express emotion or ideas in another way.”

“We also discussed the idea that self-injury should not be considered as binary, there is a spectrum of behaviour and much of it is very normal. This may help towards removing stigmas about the practice. How we define disfigurement seems to be what decides whether self-injury needs intervention or treatment.”

Week 3 Summary– The Humors

In the final week of workshops, Alanna spoke about the ancient concept of the humors. The theory was carried all the way up until the 1850’s and held the belief that the body contained four humors, blood, black bile, yellow bile and phlegm. It was believed that the balance of these humors resulted in good health, and the imbalance of them, the consequence of character, mood, and disease. The letting of each fluid (when an imbalance was presumed) was believed to coincide with the levelling back to good health.

At this point the whole group was now digitally altering their scanned sculptures (we were at different stages of making in the previous week) and once finished, we used the Augmented Reality tool to bring them into real life and move in ways a creature would. Using this whilst recording, we were able to bring context and narrative to our sculptures, they had a presence. Whether small, hiding and unassuming, or large, foreboding and crushing. We were able to insert ourselves within this narrative too and configure a physical relationship to these objects. We placed them in setting such as in forests, under flowers, over cars, or scuttling through overgrown abandoned areas.

Towards the end of the session, each group brainstormed sentences, words and audio clips to aid the narrative of their individual piece. This was then recorded through spoken word, with the audio clips edited in later, creating a video.

“…our sculpture had taken on a life of its own, growing and distorting itself when we had used certain tools. We equated this to an independent, even an alien where it just continuously transformed itself. Or an alien beneath the skin of our sculpture that was moving around it to transform our sculpture a bit like a cancer within”

“…we discussed the idea that the act of cleansing the body is not restricted to medieval humors and is also carried out in ideas of cleanses and diet fads today and whether these are considered acts of self-harm.”

“The screen recording on the app disconnects you from the process of manipulation with the model, so it looks like the model now has its own self-awareness”

“…we had a discussion around the ‘humors’, blood, yellow and black bile and phlegm. This topic brought up interesting conversations around our object in relation to what makes us, and whether purging results in a disassociation with the body. For example, once blood is purged from the body is it still us? Or once it has left the body is it no longer part of us. Alanna talked about how in the past doctors might have saved the blood from some subjects and put it in others to try and transfer certain personality traits over to different bodies.”

0 comments on “Destigmatising self-injury through art”